Cowboy Cordon Bleu

“Mommy,”the little girl asked,

“do cowboys eat hay?”

“No dear,” her mother replied.

“They’re part human.”

That little exchange appeared as one of the jokes commonly scattered throughout newspapers of the late 1880s. It probably caused a chuckle or two. The readers might have been even more amused by our modern idea of the old-time cowboy’s diet. Today, everyone knows cowboys lived on beans and sourdough biscuits, washed down with coffee so strong it could float a horseshoe. As so often happens, everyone may be wrong.

Letters, oral histories and even an old foreman’s supply list reveal a wider range of chuck wagon fare—and there wasn’t any range much wider than the roundup districts of Montana’s trail driving days.

The bit about the horseshoe may be true, though.

First, let’s narrow the field a little. Back at the home ranch, a cowboy might eat in the bunkhouse or even with the rancher’s family. In that case, the diet often included cackleberries or hen fruit—commonly knows as eggs. There could be fresh bread, homemade jams of huckleberries, or other wild fruits. A carefully tended kitchen garden might have provided potatoes, onions, and other hardy crops.

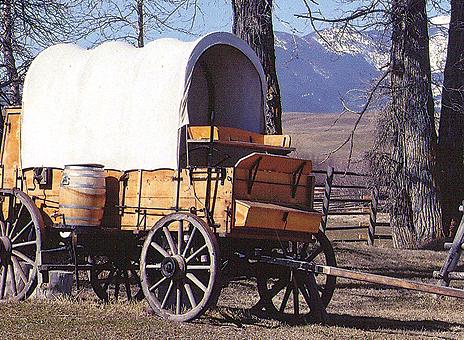

However, during the spring and fall roundups and on trail drives, that warm kitchen was miles away and meals were often eaten off tin plates, with a dozen or so cowboys hunkered down near the chuck wagon.

Why was it called a chuck wagon? It’s time to be skeptical. Certainly it is true that Charles Goodnight designed a handy storage box that became the prototype for nearly all chuck wagons. It is also true that people named Charles are often nicknamed “Chuck.” In recent years, that explanation has been widely circulated, but the term “chuck” refers to a cut of beef, which goes back at least a couple of hundred years before Mr. Goodnight’s contribution to the cattle industry. And though he was occasionally referred to in his day as “Charlie,” one is hard-pressed to find any reference to “Chuck Goodnight.”

The chuck wagon was a great improvement over cumbersome and ill-equipped ox carts, and (worst case scenario) “greasy sack outfits.” The latter consisted of a mule packed with a supply sack containing flour, beans, rice, coffee and salt pork—hence the grease.

Greasy sack outfits originated in the southwest. In the early years, just after the Civil War, no bed wagon was stacked with heavy bedrolls. Some cowboys made do with a sweaty saddle blanket spread under them in warm weather, over them on cold nights.

As the cattle industry flourished and trail herds began coming north to graze the northern plains, dining a la “cart” improved. Goodnight’s invention of the chuck box meant the cook had a place to store pots and pans, “eating irons” (commonly called knives and forks), as well as a carefully guarded bottle of snakebite remedy.

Firewood wasn’t always easy to come by, and often a cowhide sling was fastened under the wagon where wood or prairie coal could be stashed. Otherwise known as cow chips or buffalo chips, prairie coal smelled like a grass fire.

A “wreck pan” for the dirty dishes, a barrel of water and a coffee grinder were pretty much standard equipment as well. In time, some outfits even had a small stove, but variations were numerous. Most outfits had their cattle brand painted on the canvas wagon sheet or burned onto the wagon.

There were trail drives which lasted months, and roundups which lasted weeks. The cooking could be a little fancier on a roundup, when several different outfits got together to gather all the cattle in a district. Just as these roundups were the beginning of rodeo style competitions, they are probably also the forerunner of “chili cook-off.”

But that’s enough about the rolling restaurant. Let’s get to the meat of the matter.

Meat. Well, that could be a bit of a problem. The boss wasn’t particularly happy to have the hired hands chowing down on his profits. Besides, there was more meat on a steer than could be conveniently consumed before it spoiled. An injured animal which couldn’t keep up with the herd might have to be killed. A rather repellent recipe for a young calf called for the marrow gut to be included. This contained partially digested milk and was considered by some to be quite a delicacy.

Another old wheeze of the era was about the rancher who was invited to eat at another rancher’s wagon, and it was the first time he’d even eaten his own beef.

There was wild game sometimes, but firing a gun in the vicinity of a spooky herd was frowned upon. Many outfits even forbade their hands to carry guns, and careful study of the Yellowstone Journal and Live Stock Reporter shows why. Of 54 cowboys reported as seriously injured or killed over a two-year period in the 1890s, 12 were shot, most by accident and often with their own guns.

At least one rancher provided something they called pemmican, and we would call jerky. Back at his headquarters, he’d have a couple of steers butchered and the jerked meat dried over a smoky willow fire. Next he’d send a couple of men up into the mountains to pick huckleberries. Hundreds of small canvas sacks would be filled with the meat, a handful of huckleberries, and a bit of salt. Then the sacks were hit with a mallet so the berry juice would coat the meat. If a cowboy knew he’d be away from the wagon for long, he’d grab a couple of the sacks. The rancher’s grandson recalled, “It tasted pretty good, but you chewed a good long while.”

Montana’s premier cowboy, Teddy “Blue” Abbott, had fond memories from the 1880s of canned peaches and tomatoes, hotcakes, bread and biscuits, writing, “I’d never seen such wonderful grub as they had at the D H S.” Canned tomatoes stashed in a saddlebag could provide food and drink to a cowboy who couldn’t make it back to the wagon when hunger struck.

And dessert? Yep, even on the trail. Pies and cobblers could be made with dried fruit. One of the most memorable pie recipes can be found in Come An’ Get It by Ramon Adams. It wasn’t for the faint of heart —or digestion. It called for a quarter of a pint of apple cider vinegar and half a pint of water, plus “enough sugar to taste.” A good-sized lump of fat was melted in a skillet with a little flour. The vinegar mixture was added and boiled until it thickened, then it was poured into an unbaked pie crust. A lattice top was pinched on and then it was baked in a Dutch oven—a cast iron cooking pot with legs and a rimmed lid so hot coals could heat it top and bottom.

Careful experimentation has revealed that “sugar to taste” is roughly a cup and a half. If you get past the first, throat-stinging bite, you have a tangy apple-pie treat. If it’s too much for you, there’s always cowboy coffee to wash it down.

Just remember to take the horseshoe out first.

~ Montana native Lyndel Meikle is better at heating iron on a coal forge than cooking, but her vinegar pie may be to die for.

Leave a Comment Here