Running Free

The Pryor Mountain Wild Horse Range, located along the Montana-Wyoming border about 40 miles south of Billings and 13 miles north of Lovell, Wyoming, is home to a population of about 162 wild horses. Confined to the 39,000 acres that is the Pryor wild horse range, these horses are wedded to the landscape. Many are clothed with the very colors of the Pryor Mountains themselves. Horses the color of dampened limestone, faded grass, mudstone, and shaded juniper are scattered across the Pryor desert.

Rocks Grasping for the Sky

The story of the Pryor wild horses does not begin with the horses themselves; it begins with the earth on which they trod. East Pryor Mountain and its brother, Big Pryor Mountain, are distinct from their Beartooth cousins 40 miles to the west. These sloping mountains were formed by the erosion of uplifted limestone, while the Beartooth Mountains, comprised of granite, were carved by glaciers.

According to geologist Gary Thompson, writing for the Pryors Coalition, 500 million years ago much of the Pryor area was covered by ocean. Fossils and deposits in sedimentary rock indicate that the sea level repeatedly rose and fell until about 70 million years ago, when tectonic plates began to shift. The Pryor area rose from the ancient seas, with the northeast portion lifting higher than the southwest. This uneven uplift formed the Big Pryor and East Pryor mountains.

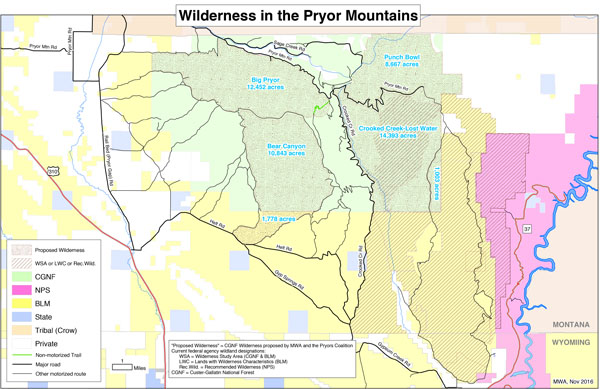

Time saw the erosion of land, which has left the pages of history exposed. Layers of sandstone, mudstone, and limestone contain fossils and other deposits. Limestone canyons and caves characterize the area, including Crooked Creek Canyon to the west and Bighorn and Devil canyons to the east.

In a lecture this spring, Montana Wilderness Association Eastern Montana field director Charlie Smillie described this singular landscape as “wild,” “sacred,” and “under-explored.” He described the rare plant communities and diversity of soil types, and how early Paleo-Indians traveled a route beginning at the mouth of Bighorn Canyon and extending southward into Bighorn Basin and into the Wind River Mountains beyond.

Somewhere surrounded by lupine and Rocky Mountain juniper, amidst the endemic blades of the Shoshone carrot found nowhere else on earth, you’ll find the Pryor horses, perhaps as distinct as the habitat they call home.

Hooves Sunk in Limestone Soil

Many of the Pryor wild horses wear their story on their backs. Most are colors known as dun, grullo, black, or bay; and dorsal stripes on the backs and zebra stripes on the legs are common. Many exhibit unique conformational features as short-statured horses with wide foreheads that taper to a Roman nose.

In 2013 geneticist Gus Cothran of Texas A&M University conducted a genetic analysis of the Pryor herd in order to help the Bureau of Land Management develop localized management strategies. Cothran, who’s tested virtually every BLM-managed herd in North America, found through comparative analysis that, while the Pryor horses do show a mixed lineage, they appear to have direct Colonial Spanish ancestry.

“In terms of current free-living wild horses, the Pryor herd is one of a very, very small number that actually do show strong indication of old Spanish ancestry,” Cothran said. “There’s just a handful.”

It is this unique heritage that draws many to the Pryor horses, including Christine Reed, professor of public administration at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. “For the most part, wild horses are escaped ranch horse stock or cavalry stock, but the Pryor horses have a unique Spanish lineage,” Reed said, describing what interested her about the Pryor herd before writing her 2015 book, Saving the Pryor Mountain Mustang: A Legacy of Local and Federal Cooperation.

A small shipment of domesticated horses accompanied Christopher Columbus and his men as they set out for the ports of the West Indies on their second voyage in 1493. Within 200 years, feral horses munched the grasses from Argentina to Canada.

“People aren’t exactly sure how the horses got from the New Mexico/Texas area up into Montana, but they think it was probably a trade route used by Native American horse traders,” Reed said.

It is likely around the seventeenth century that feral horses rolled in the grass of East Pryor Mountain, sunk hoof in the limestone soil, and drank from the waters of Bighorn River.

Ever as Before

The next chapter in the story starts in the 1960s during a national debate over the definition and management of lands and land use. Wild horses were rounded up for permanent removal as a species threatening livestock, wildlife, and plant ecosystems. Advocates sought protection for wild horses across the country.

“You either love them or you hate them,” Crow Elder and historian

Howard Boggess said. “I love them.”

Howard Boggess grew up on the Crow Indian Reservation and remembers seeing the wild horses in the Pryors well before the area was a federally designated horse range.

“We used to ride horseback and cross Bighorn Canyon and wild horses were there,” he said.

In 1968 former Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall established the Pryor Mountain Wild Horse Range, an action that predated national legislation protecting all wild horses by three years. Nearly 50 years later controversy over the management of the horses continues, something well tracked by newspapers and advocacy groups alike.

It is somewhere in between these voices and reports that the Pryor horses find themselves today, grazing on the spring grasses of Mustang Flat, sipping water from the Bighorn River, or sunning themselves on the slopes of East Pryor Mountain, breathing in the air of a truly spectacular place.

Beyond the Horses

The Pryor area is geologically, ecologically, meteorologically, and culturally unique, and the wild horse range encompasses only a small portion of the region. Access the Pryor Mountains through Bridger or Warren, Montana, and Cowley or Lovell, Wyoming.

Botanists treasure the diversity of plant species in the Pryors as they are home to rare plants that don’t grow anywhere else in the world. The Pryors comprise the northern limit of many plant species’ ranges.

The area is also rich in cultural history, containing hundreds of archaeological sites that include tipi rings, quarry sites, vision quest structures , and cave and rock shelter sites.

To learn more about the rich Pryor Mountains visit pryormountains.org