It Takes a Village: The Conservation of the Blackfoot

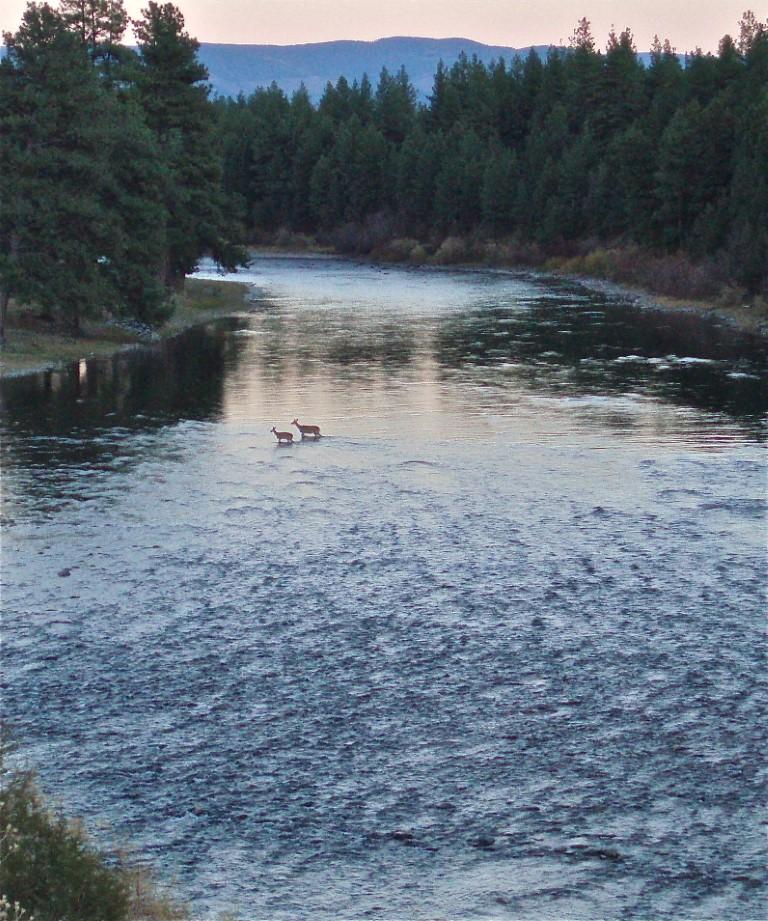

Photo by John N. Maclean

There is an African proverb that states it takes a village to raise a child. It might also be true for rivers.

The Blackfoot river extends 132 miles from the Anaconda creek near the top of Roger's Pass to the confluence with the Clark Fork river by Missoula Montana. The watershed encompasses 1.5 million acres where seven communities work, recreate, and have endured the challenges created by years of poor mining practices, logging, livestock grazing, and a growing number of recreationalists. As I drove Highway 200 towards Ovando, I crested a hill and the valley below shined brightly in the midday sun. Shadows were casting off the ponderosa pines standing tall and proud towards the deep blue sky. Off to the north, the jagged peaks of the Scapegoat Wilderness were competing for the clouds that kept playing in-between the saddles and ridgeline.

I parked along a stretch of dirt road where I could see the valley and the mountains between the trees, turned off the truck, and stepped out to silence and crisp spring air. There was something here I could not put into words, something that felt wild and uninhibited. A coyote did not appreciate my appearance and silently took off up the slope before disappearing into the brush. I could sit there all day taking in the surroundings but knew I was pressed for time. I had to meet Blackfoot Challenge and the Riverkeeper of the Blackfoot, so I said goodbye for now and headed back to the pavement and town.

Ovando sits in the heart of the Blackfoot watershed and has a population of 64. The Blackfoot Challenge has been running its non-profit here since 1993. The day I arrived, Sara Schmidt, their communications manager, and Randy Gazda, retired fish wildlife and service and now serving as vice-chair, were giving a group of high school science students from Helena a talk on their conservation efforts. The Blackfoot Challenge united landowners and public agencies, forming a community that would support each other and uphold the values of the area. They wanted to get ahead of the curve on the problems they were facing; the non-profit American Rivers listed the Blackfoot as one of the most endangered rivers in the nation.

Photo credit: Hallie Zolynski

The Mike Horse Dam, located at the river's headwater by Roger's pass, breeching and spilling toxic mine waste downriver in 1975. It became a superfund site, but the damage was done. Fish, Wildlife, and Parks even wrote off the river and would not do any fish counts. Finally, through persistence and a $39 million settlement with Atlantic Richfield Co., funding became available for a reclamation project.

So far, it is paying off as the Blackfoot is showing a thriving fish population. Through efforts from the Big Blackfoot Trout Unlimited and Blackfoot Challenge in the early 1990s, seed money, and numerous meetings with community members and government agencies, the community was made aware of the problems and headway was made. The dam was removed, and work is still underway to reclaim the river.

Over the years, the non-profit has become a thriving stewardship featuring 25 current board members. Their projects include the re-introduction of Trumpeter Swan, establish a 5,600 acre area set aside for critical wildlife habitate called the Blackfoot Community Conservation Area (BCCA), bringing fire back onto the landscape, introducing the industrious beaver back to restore wetlands, and helping landowners use non-lethal ways of dealing with grizzly bears and wolves.

Their motto is simple: Invite everyone to the table and start by building trust and respect over good conversations. As one student in the back of the hall said, "It's organizations like yours that make Montana pretty." Their teacher has been bringing students here for over ten years in the hopes that they will stay, work and raise families in the area and keep the spirit of the Blackfoot alive. Today the Blackfoot Challenge has become one of the most significant driving forces of conservation of the Blackfoot watershed.

In the afternoon, I was to meet with the Big Blackfoot Riverkeeper but I had time to spare, so I walked into the general store/Inn/Espresso Bar and chatted with a local who recently moved back into the area. He told me how he used to be able to get off work back in the day and fish without seeing anyone. Now he says, rafts compete for spots along the river, and people who do not understand conservation are coming from all over. He was not happy about it, substantively the same sentiment I found among the locals at Trixi's Antler Saloon.

Photo Credit: Hallie Zolynski

I had also been corresponding with John Maclean, Norman Maclean's son. His new book is called Home Waters: A Chronicle of Family and a River, and he hopes it will bring change and restore some sense of dependable serenity to the Blackfoot River. I asked him his thoughts on recreation on the river, and he told me that the Blackfoot used to be a remote, little known waterway before the book and film adaptation of A River Runs Through It made it as legendary as rivers like the Madison and Missouri, and in some ways more so. The effects have been both good and bad.

The river used to be impoverished but has come back as a fishery thanks to contributions and enormous work by local groups and individuals. But so much attention on the river has resulted in overuse. He says that it is not the river of his youth having been overrun by boats, anglers, and gawkers, and that his dad had complained about the "Spanish Armada" of boats coming down the river even in his day.

He tells me about a favorite fishing hole his family has used for generations called the Muchmore Hole and how people will bypass every other hole to get to that one and then sit for hours fishing it, using treble hooks - legal but, in his opinion, unsportsmanlike behavior. Worse, people will trespass to get to the hole, and in Montana, that is taking a chance at getting shot at.

With this in the back of my mind, I met up with Jerry O'Connell, the Big Blackfoot Riverkeeper. I sat in his truck as he weaved around crater-sized potholes, stopping at areas where the Lewis and Clark Expedition passed through and giving me a history lesson at each one. I could tell he took some pride in his storytelling. It made the afternoon enjoyable; he's quite the character, full of enthusiasm and overflowing with knowledge of local lore and conservation issues.

Between history lessons, he told of how he first came here in 1986 and fly-fished the Blackfoot, hitchhiking to Missoula and jumping on trains to get around. He says that an area of particular concern right now is a 6-mile stretch of the river enjoyed by rafters that run from Whitaker Bridge to Johnsrud Park. The Bureau of Land Management has recently approved to pave roads to the spot, but there is hope this will not happen, and the road will remain just as bad as it was on the day we went. If it does get paved, the fear is more people will come to the river, and with them the potential for more problems.

As we made our way down the road at one spot, he stopped to talk about boaters making camps along the river and the damage it was causing. Collaborating with MFWP, their solution was the Blackfoot River Float-In sites, a series of 11 reservation-only campsites dedicated to float-in camping along a 70 mile stretch of the river which has no vehicle access. Each camper is required to practice a complete pack in/pack out, zero-waste mentality. Jerry said it is a start in trying to keep the river clean and hold recreationalists responsible.

Speaking with Maclean, O'Connell, and the staff of the Blackfoot Challenge impressed on me that the Blackfoot watershed has been called the Crown of the Continent for good reason - in many ways, the landscape and the wildlife remains relatively unchanged since the Lewis and Clark expedition. With ongoing efforts from local conservation groups, community members, and government agencies, this area so beloved by Norman Maclean, which many call a watercolor landscape, will stay intact for future generations to enjoy.

SIDEBAR: I would like to thank John Maclean for the photos, personal experiences and the advanced copy of Home Waters, Sara, Randy and everyone at Blackfoot Challenge for all their work and dedication and Jerry the Big Blackfoot Riverkeeper for taking me along a beautiful stretch of river and having such enthusiasm, not to mention keeping me entertained with anecdotes and historical tidbits.

Please visit https://blackfootchallege.org and https://bigblackfootriverkeeper.org for how you can get involved and read more on the conservation of the Blackfoot.

Photo Credit: John N. Maclean