The American Dream Home By Mail: Kit Homes Out West

Graphic by Rob Rath

Imagine that the year is 1910 and you have just moved with your family to Montana. The last spike of the Milwaukee Road was driven in last year just west of Garrison, and the small town where you live is now accessible by rail from both the West Coast and the distant metropolis of Chicago.

With the advent of rail transportation comes an unexpected opportunity: the chance to buy and build a relatively affordable home for your growing family. A mail-order company will ship on a sealed boxcar everything you need—pre-cut lumber, doors, windows, flooring, trim, even the nails and paint. All you need to do is put down a modest down payment, go down to the train station to pick it up, and slap it together on the land you’ve just bought with your hard-earned savings.

For many Americans, mail-order houses or “kit homes” provided an unprecedented opportunity to become homeowners. For just as many people, though, the popularity of mail-order homes signified an existential threat whose closest comparison today would be the competition Amazon poses to local businesses. The nostalgia for kit homes that has cropped up in the past few decades overshadows the reality of how these homes, and mail-order companies in general, were perceived by communities across the country, especially in rural places like Montana.

Sears, A Behemoth Among Giants

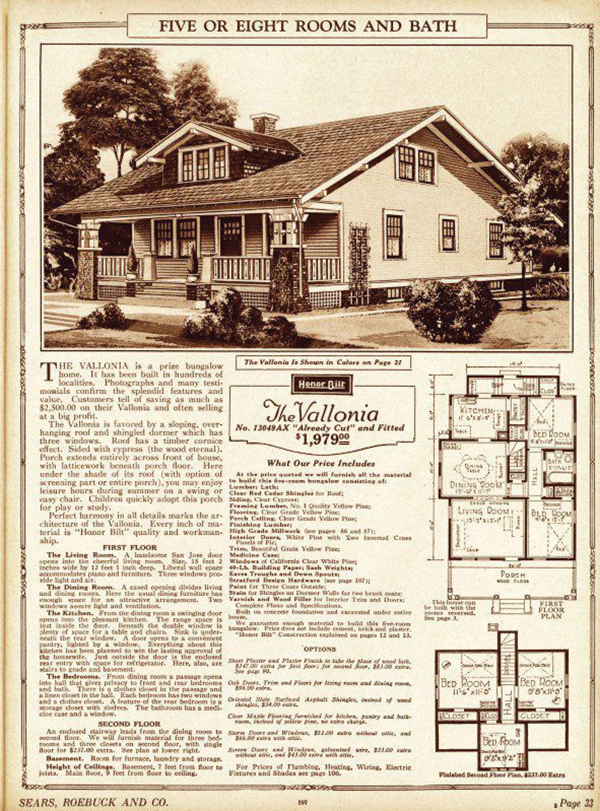

Sears Roebuck and Company is the name that comes most easily to mind when kit homes are mentioned. Its eponymous catalog offered everything a person could want or need (or not need) for their domestic and entrepreneurial endeavors. Sears used the popularity of its general merchandise catalog to market its new home department to consumers.

The Sears Modern Homes Catalog launched in 1908, offering 22 floor plans that ranged from $650 to $2,500, including all 30,000 pieces and a booklet of blueprints, instructions, and materials list. These first houses could not be properly called “kit homes,” because the timber was not pre-cut. Sears provided the lumber, but the customer had to cut it themselves. Aladdin was a Michigan-based mail-order company who sold pre-cut framing boards from the start in 1906, and Sears ended up adopting their competitor’s “ready-cut” model in 1916.

The Sears Modern Homes Catalog launched in 1908, offering 22 floor plans that ranged from $650 to $2,500, including all 30,000 pieces and a booklet of blueprints, instructions, and materials list. These first houses could not be properly called “kit homes,” because the timber was not pre-cut. Sears provided the lumber, but the customer had to cut it themselves. Aladdin was a Michigan-based mail-order company who sold pre-cut framing boards from the start in 1906, and Sears ended up adopting their competitor’s “ready-cut” model in 1916.

Between 1908 and 1940, Sears sold about 100,000 kit homes to Americans across the country. The other three national companies—Aladdin, Montgomery Ward, and Gordon Van-Tine, along with a slew of smaller regional companies—account for maybe a couple hundred thousand more. Considering the population of the United States and the overall number of homes getting built, this doesn’t sound like a whole lot. It’s estimated that kit homes account for only 2-5% of all American homes built in the 1920s. Pamela Attardo, the heritage preservation officer for the Lewis & Clark County Heritage Tourism Council, knows of only one definitive Sears home in her jurisdiction, a Modern Home No. 115, built before 1912 in York.

Despite these modest numbers, kit homes have left an outsized imprint upon the American imagination, as the revitalized interest in their history over the last few decades attests to. Why is this? What is it about mail-order homes that we find so alluring? Could it be nostalgia for a bygone era? The undying romance of the DIY lifestyle? Or is it simply the most American aspect of the whole phenomenon, the seduction of consumer convenience?

Graphic by Rob Rath

The Heyday of Mail-Order Homes

Different companies dominated the market in different parts of the country. Sears, Lewis, Sterling, and Harris Brothers served the East Coast, South, and Midwest. The West Coast was dominated by Pacific Homes, Montgomery Ward, and Gordon Van-Tine. Aladdin had its fingers in all these markets, as well as in Canada, thanks to eventual production facilities in Oregon, North Carolina, and Mississippi. Even more companies operated at smaller regional and local levels.

The market for mail-order homes peaked in the 1920s, in the reprieve years between World War I and the Great Depression. The relative affordability of kit homes was one factor in their success. Kits ranged anywhere from $400 to $3,500 and helped members of the working class and burgeoning middle class achieve homeownership, a key element of the mythological American Dream. What’s more, a few companies including Sears and Montgomery Ward even offered mortgage financing with their kits, making it even more affordable for people of color and single women to secure financing when they were legally or illegally barred from doing so through banks.

The market for mail-order homes peaked in the 1920s, in the reprieve years between World War I and the Great Depression. The relative affordability of kit homes was one factor in their success. Kits ranged anywhere from $400 to $3,500 and helped members of the working class and burgeoning middle class achieve homeownership, a key element of the mythological American Dream. What’s more, a few companies including Sears and Montgomery Ward even offered mortgage financing with their kits, making it even more affordable for people of color and single women to secure financing when they were legally or illegally barred from doing so through banks.

Another factor that sealed the deal was convenience: the mail-order company shipped by freight or boat everything you needed to build a home, and would even provide plumbing, kitchen and electrical fixtures at an extra cost. All you had to do was put it together, which catalog testimonials claimed was unbelievably easy to do in under 90 days, or at worst, hire a contractor to do it for you. According to architectural historian Rebecca Hunter, most people did end up hiring contractors. The testimonials exaggerated the ease of product assembly, just like all good marketing ploys do. You still had to know something about carpentry to put your house together, especially before the invention of power tools.

Marketing to the Conformist

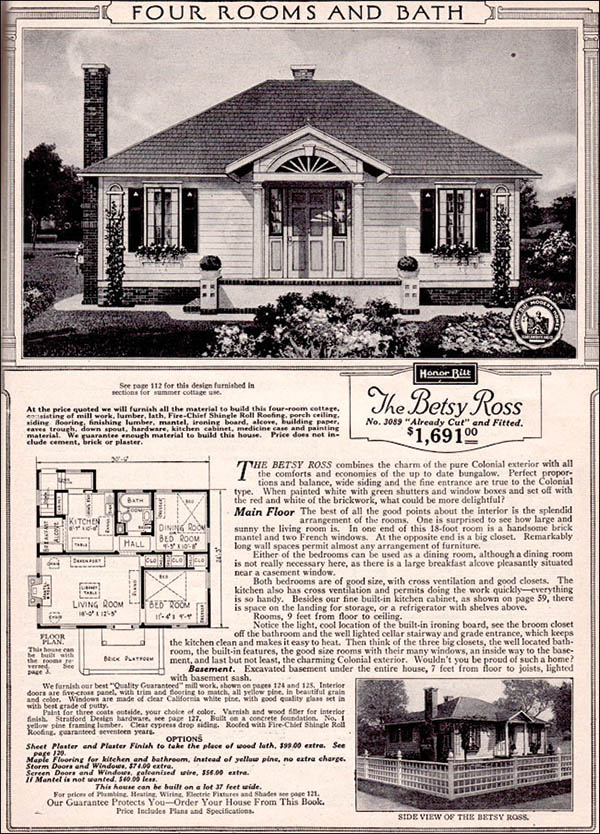

Marketing strategies centered around the consumer desire for a house that was both cheap and would pass as a custom-built home. Aesthetic innovations were not a priority in kit homes, which is largely why they can be so hard to identify walking around your neighborhood: they were purposefully designed to look like the most popular styles of the day.

Some of the commonly occurring descriptions in the Modern Homes Catalogs are “harmonious,” “convenient,” “practical,” and “economically constructed.” The consumer’s desire for conformity was catered to with such phrases as “a touch of individuality” and “not too extreme.” Many companies, though, offered customizable options, like reversed floor plans, add-on porches or sunrooms, and choice of paint and trim colors. While most early designs were known only by their model number, companies eventually started naming their products. Many had women’s names like the Chelsea and the Betsy Ross, but the Starlight, the Sunbeam, the Fairy, and the Americus were some of the more fantastical monikers at Sears.

Graphic by Rob Rath

Local Pushback in Montana

Not everyone was thrilled with the burgeoning popularity of kit homes. Local businesses routinely ran advertisements decrying the export of local dollars to mail-order companies based out of state who didn’t have to pay local taxes. Sound familiar?

In papers like the Billings Gazette, the Ravalli Republic, and The Missoulian, advertisements, letters, and editorial columns attested to the widespread backlash against mail-order companies in the early twentieth century. In 1925, the All-Montana Development Association sponsored a letter-writing contest as part of its Buy-At-Home campaign. Taking first place and the hundred-dollar cash prize was Lester Byron, a rancher in Lincoln County, who lamented that “the dollar you spend away—is a dollar gone. The dollar you spend at home—is the dollar that adds power and production to Montana.”

In papers like the Billings Gazette, the Ravalli Republic, and The Missoulian, advertisements, letters, and editorial columns attested to the widespread backlash against mail-order companies in the early twentieth century. In 1925, the All-Montana Development Association sponsored a letter-writing contest as part of its Buy-At-Home campaign. Taking first place and the hundred-dollar cash prize was Lester Byron, a rancher in Lincoln County, who lamented that “the dollar you spend away—is a dollar gone. The dollar you spend at home—is the dollar that adds power and production to Montana.”

Aladdin infrequently ran advertisements in Montana papers that proclaimed “30% saving on labor” and “18% saving on lumber.” But much more common were advertisements from coalitions of “public-spirited citizens,” or business owners, protesting the incursions of catalog houses on the local market. Historic preservationist Paul Putz of Townsend explains that the pushback from local business communities was there from the beginning—not just against kit homes, but against all mail-order products. A July 17, 1927 article in the Helena Independent paints a facetious picture of one hypocritical citizen “on the way to the mail box [sic] with a fat mail-order blank in an envelope with his check, and the song ‘Keep the Home Fires Burning’ on his lips.”

In the Billings Gazette on March 24, 1919, Thompson Yards ran an ad that directly compared their prices to those of mail-order houses from Gordon Van-Tine, Sears, Aladdin Readi-Cut, and Harris Brothers. The difference in each instance was about $200 in favor of Thompson Yards. “Notwithstanding the fact that most mail order houses claim to be able to save the user of lumber from 30 per cent to 50 per cent,” the ad grudgingly concedes, “it is quite evident that their claims are not intended to apply to towns where we operate a Thompson Yard.”

The Slow Decline of the Kit Home Empire

All the national companies put their kit home departments on hiatus in WWI when building materials were requisitioned for wartime use. Aladdin and Lewis were two examples who kept afloat by contracting with the military for barracks construction.

The biggest year for kit homes across the country was 1928-1929, when companies began catering to suburban and urban customers over rural customers. Then Black Monday happened, and the Great Depression induced a slump in sales for several years. Those companies who offered mortgages had their ingenious idea backfire on them when they had to foreclose on their own customers. Though the Great Depression was not exactly a death knell for the kit home industry, it was the beginning of the end. The industry enjoyed a brief resurgence in the late thirties before World War II, when materials were again requisitioned.

The post-WWII housing boom proved too little, too late to return the industry to its former glory. Sears closed its Modern Homes department in 1940, and after selling 37,000 homes west of the Rockies, Pacific Ready-Cut Homes transitioned to making surfboards after WWII. Montgomery Ward had already put the kibosh on its kit home department in 1931 after selling a total of about 30,000 homes. Hanger-on Aladdin continued selling kit homes through 1983, for a total of about 100,000 houses.

The self-sufficiency and individualism of the American West ultimately proved at odds with the do-it-yourself culture appropriated by catalog companies for their own profit. This is a surprising revelation given the romance surrounding the history of kit homes, as well as the pretty minimal financing requirements that mail-order companies asked of people who otherwise would not have been able to afford to buy a home. On the other hand, it is not surprising at all when the contrarian and community-minded spirit of the average Montanan is considered.

Authenticating kit houses is notoriously difficult, given how few are left standing, renovations that may have changed their appearance, and how similar they look to popular designs. If you are interested in finding out whether your home might be a kit home, a good place to start is with a search of grantor records at your county courthouse. If a mortgage was ever held by Sears or Montgomery Ward, it will likely be recorded. You might also look for stamped lumber or shipping labels in basements, attics, and other out-of-the-way corners.

Other resources to acquaint yourself with visually identifying kit homes or learning more about their history are Finding the Houses that Sears Built by Rosemary Thornton, America’s Favorite Homes: Mail Order Homes as a Guide to Popular Early 20th-Century Houses by Robert Schweitzer and Michael W. R. Davis, and Mail Order Homes: Sears Homes and Other Kit Homes by Rebecca Hunter.