“Give me a high drop, boys” - Frontier Justice and the Ghost of Henry Plummer

Lynching at the hands of a group of self-appointed vigilantes was employed in many mining towns across the Western U.S. in the mid-nineteenth century, including Montana. With the legal structure of courts, lawyers and judges lagging well behind the growth and the ensuing lawlessness of each gold strike, expedience was sometimes the preferred instrument to establish “law and order.” This so-called “law,” on more than one occasion, was one of hanging individuals based on suspicion alone. However, one cannot deny that some sort of “order” was established, and rather quickly at that.

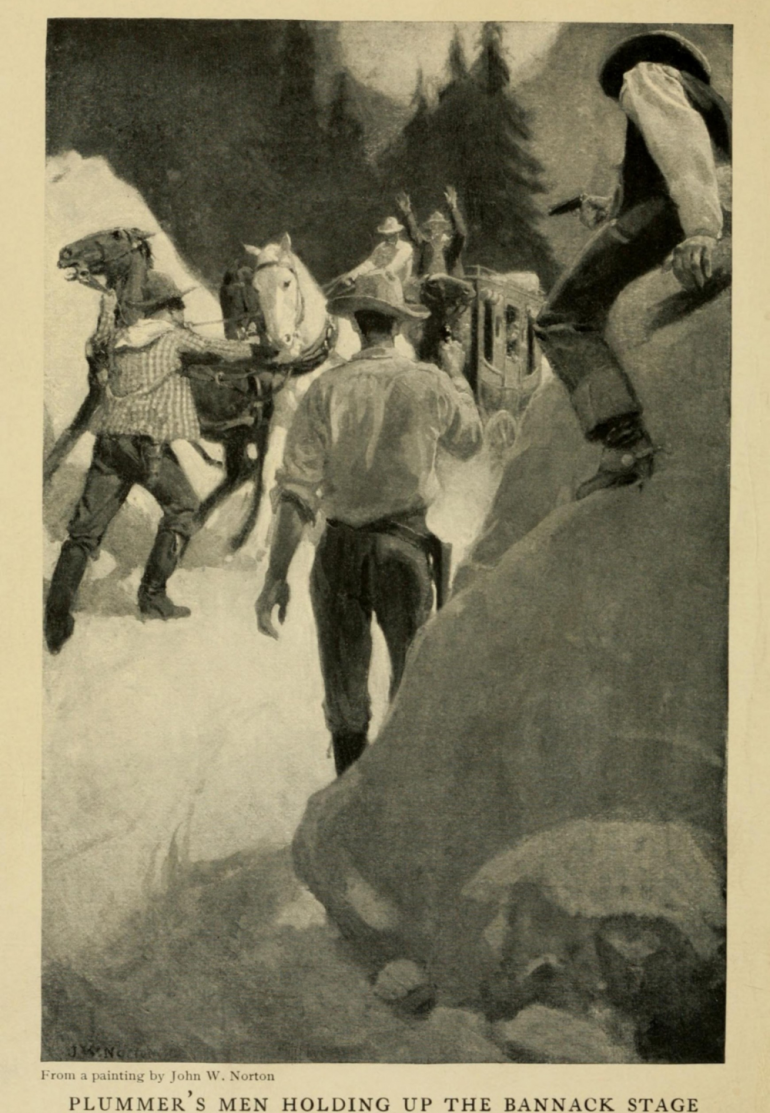

This brings us to Henry Plummer. Plummer has held a central position in Montana lore for over 150 years, becoming a larger-than-life figure as the freely elected sheriff of Bannack who was hung by vigilantes in January, 1864. He had no trial and there was no real, physical evidence to back up the accusations made against him. In those days, suspicion alone, or the wrong political allies, could be enough to earn the donning of a “rope necktie” from the nearest cottonwood tree. Anyone foolish enough to criticize them could also be quickly strung up, so for years only the vigilantes’ side of the story was told.

Historians at the time painted Plummer as a cold, calculating outlaw who headed an elaborate band of desperadoes, while the vigilantes were heroes, just trying to establish order during the rather lawless times of the mining camps of the 1800s. More recent examination of these events makes it clear much of what was written then was filled with exaggeration and bias, casting much doubt on such simplistic interpretations. If nothing else, Plummer was a complicated man, not given to easy interpretations.

It seems people either really liked him or hated him. That distinction usually fell along party lines. Plummer was a self-professed Democrat, and supported the “states’ rights” platform of the South, though certainly not their pro-slavery plank. He regularly advocated for the rule of law and was publicly against vigilantism. He associated more with those of the lower economic strata, such as miners and other wage earners, and, others would also add, often with those of dubious character. Republicans tended to be the more wealthy businessmen in the community. In the run-up to the Civil War, and certainly during the years of that conflict, there was great suspicion, animosity and violence between Republicans and Democrats. The press was openly either pro-Republican or pro-Democrat, regularly slung defamatory accusations at one another, and were often responsible for inciting violence from their followers. This was especially heightened during the Civil War years.

Photo by Doug Stevens

Plummer came to Bannack in 1862 with baggage—and I don’t mean suitcases. In 1852, at the age of 19, he left his native Maine for the gold fields in California. After nearly 10 years on the west side of the divide, he arrived in Bannack with a criminal record (murder, commuted) and a bad reputation. Literally, trouble seemed to follow him like a long, dark shadow. The company he kept did little to assuage the rumors.

However, Plummer was very charismatic and possessed unique leadership skills that even his detractors admired, and he was readily elected Bannack’s sheriff in May 1863. The hours were long and the pay was terrible. It was a job few wanted, but Plummer embraced it—and the standing it gave him in the community. He had even successfully applied to be a deputy territorial marshal, much to the chagrin of his enemies. However, news of his pending appointment unfortunately came too late, shortly after his hanging.

More recently, some historians have concluded that Plummer was not only innocent, but that his hanging was politically motivated. The executive committee of the vigilantes was made up of well-to-do businessmen of the area—all Republicans. Many of them also harbored political ambitions in what soon would be the new Territory of Montana. They may have seen the charismatic Plummer as a political threat. Additionally, Plummer was known to own stakes in many of the area mines and was considered to be quite well off, so it is also interesting to note that it was vigilante policy to appropriate all their victims’ assets—supposedly to pay for their prosecution and burial! When it comes to Plummer, there is no record of who got what of his substantial estate. More than 150 years later, the truth about Plummer, and his role in the area robberies, is now probably irretrievable.

Finally, on May 7, 1993, Sheriff Henry Plummer received his long-overdue trial, of sorts, in Virginia City. As part of a “living history” class, the Twin Bridges Public School District staged a posthumous trial. Students were each assigned a character from the original saga and responsible for “becoming” them, so they could accurately act out their parts in the courtroom. The mock trial was presided over by a real judge, and 12 locally registered voters made up the jury. “Witnesses” took the stand, and the prosecution and defense presented their evidence (such as it was). In the end, the jury was split on the verdict 6-6. I suppose it was a foregone conclusion that the trial would result in a “hung jury!” Had Plummer been alive, he would have been freed and not tried again.

Bannack is now a state park, complete with a campground, and open to visitors year-round to explore its history firsthand. The jail that Plummer built is still there, though the simple gallows have long since deteriorated and been replaced by a replica. However, nothing is left of Yankee Flats, that part of town on the south side of Grasshopper Creek where a sick Plummer had been staying with his brother and sister-in-law, suffering from a relapse of his childhood “consumption,” when he was taken to the gallows that fateful night.

And so, on a cold night, January 10, 1864, the vigilantes having hung his two deputies before him, it was now Plummer’s turn. After he uttered his final words, “Give me a high drop, boys,” the vigilantes obliged, and in an instant, with a snap of the rope, his life was extinguished. Plummer was only 32. The bodies were left hanging overnight in sub-zero temperatures, freezing solid. The next day they were laid out and sketches were made of the three dead law officers before burial in shallow graves in Hangman’s Gulch, near the gallows that Plummer himself had built.

What happened next to Plummer’s body has become something of folklore, as colorful as his mortal life. Legend has it that some time later, the town doctor, Dr. Glick, exhumed the body to amputate the right arm. Glick was curious about the shotgun slug Plummer had taken in the right elbow a few months earlier. It is reported that he found the slug in his wrist and that it had been “worn smooth and polished by the bones turning upon it.” Later, a little before the turn of the century, it is said that two visitors dug him up again on a dare. To prove they actually accomplished the task, they cut his head off and brought it back as a trophy, where it is said to have been on display at the Bank Exchange Saloon for several years, until the bar burned down in 1898, taking with it all its contents. Such indignities are obviously more than enough to turn any self-respecting spirit to haunting!

So, if you find yourself wandering the streets of Bannack at night (which you are not supposed to do, as the park closes at sunset), you might just see a one-armed, headless apparition. Watch out—it’s the ghost of Henry Plummer, and if you’re a Republican, I suggest you run: he might be out for vengeance!