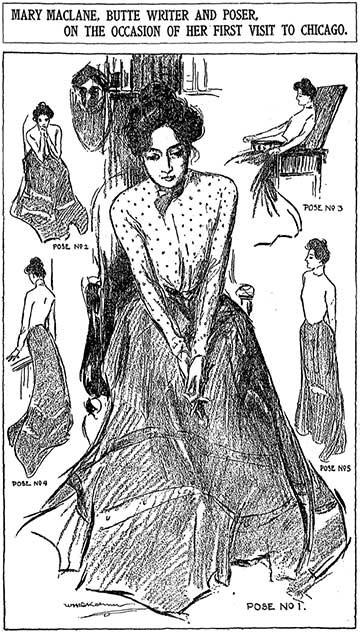

"I Await the Devil's Coming": Mary MacLane, Butte's Prodigal Daughter

Chicago publisher Herbert S. Stone & Co. released I Await the Devil’s Coming in 1902, Mary MacLane’s first memoir written when she was 19. Although it was issued under the much less provocative title The Story of Mary MacLane, the content was so sensational, so intimate, so blunt and unapologetic, that people couldn’t help but have strong opinions, especially the people of Butte, whose scorn for MacLane’s scandalous and unladylike behavior—which included her open bisexuality and frequent appeals to the Devil for deliverance from her monotonous, lonely existence—nearly equaled her own contempt for the former’s petit-bourgeois mentality.

“Butte and its immediate vicinity present as ugly an outlook as one could wish to see. It is so ugly indeed that it is near the perfection of ugliness. And anything perfect, or nearly so, is not to be despised.” As a teenager in Butte at the turn of the twentieth century, Mary MacLane took long walks day and night through the city. It was a place where she felt entrapped, misunderstood, and maligned—feelings that were not misplaced, considering the fraught relationship with Butte that her later notoriety would engender.

I Await the Devil's Coming

Had she still been alive when dubbed a “Montana” writer, MacLane would have been horrified. The typical fare of Western literature—rugged landscapes and stoic people—inspired only boredom and disdain. MacLane does not present nature as a nurturing, restorative place from which she benefits spiritually and creatively. She instead implies that she succeeds in expressing herself, in envisioning another future, despite her environment. She writes, “I have reached some astonishing subtleties of conception as I have walked for miles over the sand and barrenness among the little hills and gulches. Their utter desolateness is an inspiration to the long, long thoughts and to the nameless wanting.”

MacLane revels in Butte’s ethnic diversity, noting that “there are not a great many people—seventy thousand perhaps—but those seventy thousand are in their way unparalleled. For mixture, for miscellany—variedness, Bohemianism—where is Butte’s rival?” She mentions the Irish, the Cornish, the Africans, Italians, Finns, French, and Native Americans: “A single street in Butte contains people in nearly every walk of life—living side by side resignedly, if not in peace.” But this does not excuse Butte’s shortcomings. For all that it bustles with activity, it’s not the kind of activity that appeals to her. Mere pages later, MacLane puts it frankly: “The souls of these people are dumb.”

The bone she has to pick with Butte, and with people in general, has to do with the tyranny of middle-class mores. Her humor is so cutting and dry that it’s no wonder people felt insulted. “From wax flowers off a wedding-cake, under glass; from thin-soled shoes; from tape-worms; from photographs perched up all over my house; Kind Devil, deliver me […] From people who persist in calling my good body ‘mere vile clay’; from idiots who appear to know all about me and enjoin me not to bathe my eyes in hot water since it hurts their own; from fools who tell me what I ‘want’ to do: Kind Devil, deliver me.”

MacLane's Residence on Excelsior Street in Butte. Photo by Lindsay Dick

A Divided Reception

The local media lambasted her on a regular basis, even after the proceeds from her bestselling memoir enabled her to leave Butte for more cosmopolitan pursuits on the East Coast. The public library even banned her book from its shelves. Some editorials denounced her for her immoral conduct; others went so far as to call her a fraud who was out to make a quick buck by capitalizing on the public’s appetite for sensational material.

While Butte refused to acknowledge MacLane’s literary integrity, the rest of the country lauded her for her creative genius and honesty. With the release of a second memoir in 1917, the Daily Missoulian ran a reprint of a Kansas City Star editorial wherein MacLane’s critics were essentially accused of lacking moxie and imagination: “Critics and such who have not the courage to say just what they mean find ready refuge in the handy word, ‘erotic.’ [...] Frankness is [MacLane’s] stock in trade. As was said of a famous revolutionary orator she dares to say what others scarce dare to think.”

It is this last trait of hers that fueled a resurgent interest in MacLane among feminist scholars in the 1970s. In a 1977 article in Montana: The Magazine of Western History, archivist Carolyn J. Mattern cites early twentieth-century literary critic Barrett Eastman, who wrote that “all women feel, but few know what or how or why. Mary MacLane knows and is not afraid to say.” Although she read feminist literature and was acquainted with members of the Butte suffrage club, MacLane was not an active feminist. Being the misanthrope she was, she eschewed group activities, including political ones. But as a woman who fearlessly expressed all her emotions and desires, her posthumous importance to the feminist movement is undeniable.

Mary MacLane, standing, and her family.

I, Mary MacLane

After several years writing for large newspapers, living with Caroline Branson, the former lover of writer Maria Louise Poole, and releasing a flop of a second novel, My Friend Annabel Lee, MacLane was hustled back by her stepfather to Butte in 1909 after falling into financial ruin. She came down with scarlet fever, which left her in fragile health. In 1912, she started writing her second memoir, I, Mary MacLane. It is a more measured and ruminative work, although the incandescent fury that characterizes I Await the Devil’s Coming still shows itself on occasion.

From her family’s house on North Excelsior Street, MacLane could see the Anselmo mine and watch the miners change shifts. In I, Mary MacLane, she explains her relationship with language in a way that recalls both the synesthesia of the poetic mind and the laborious process of mining. She notes, “I see two words which may be the only proper ones out of ten thousand to bear my thought,” much like Butte miners picked through layers of bedrock for copper veins. She discusses how she orders words by tiers, making choices based on her audience and the desired effect. As twentieth-century critic H. L. Mencken noted, MacLane is keenly aware of the explosive power of words: “I use discretion. I know that tier of words to be of the nature of bombs, of strychnine, of a dynamic force resistible against all human and worldly substance.”

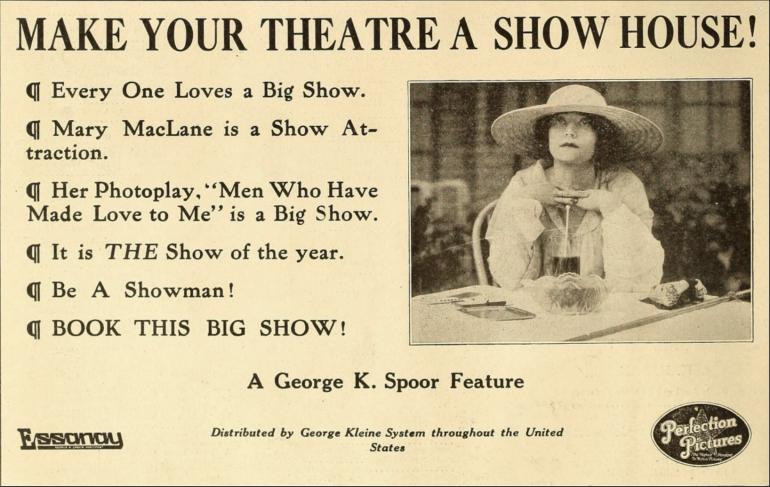

Although she left Butte for a second time, MacLane never again experienced the fame and financial comfort that her first book had secured for her. She did write, direct, and star in the semi-autobiographical silent film Men Who Have Made Love to Me, which includes the earliest recorded instance in serious cinema of breaking the fourth wall. The film unfortunately has been lost. She died alone in a seedy hotel room in Chicago at 48 years old in 1929. When her body was found, she was reportedly surrounded by newspaper clippings from her glory days, although this rumor may be more rooted in exaggeration than fact.

Mary Maclane. Source: The Mary MacLane Project

The Gray-Purple

The reader must wait for the last twenty pages of I, Mary MacLane, to at last experience her confession of love for Butte. The entry is entitled “The Gray-Purple,” and that it isn’t quoted more often in anthologies of American or Montana literature is to the detriment of both those canons. It is exquisitely written and worth reading in its entirety:

“[Butte’s] insistent charm is that it goes on strongly resembling itself year after year [...] I am profoundly lonely in it: my life-tissues are long familiar with the feel of it: its mournful beauty has entered like thin punishing iron into my Soul: and my love for it is made of those things. For no reason I feel love for this Butte.

“As much as for the mountains in their mourning intimateness I feel love for all the outsides and surfaces of the town itself [...] the little mines in unexpected mid-town blocks with their engines and hoists and scaffolds and green coppery dumps [...] The edge of Walkerville, the surprising steep Idaho Street hill, the North Excelsior Street neighborhood where I wrote my Devil and Gray-dawn book […] the markets on the afternoon shade side of West Park Street full of crabs and lobsters from Seattle and shining fish from California […] All of it has a feel of something aloof and metallic and distinctive and gray-purple and Butte-Montana.

“[...] Its wonderful Aridness starves human nerve-soil till the sad wide eyes of the Soul grow bright—fever-bright, light-bright, star-bright—from denial and unconscious prayer: involuntary worship: homage of the unsuppliant unhoping devotee.”

For all that she is accused of being self-absorbed, what characterizes MacLane as a writer is her awareness of her own fallibility.. Of her writing, she laments, “It is as if I have made a portrait not of me, but of a room I have just quitted.” Although she is not known for her brevity, here she expresses succinctly the frustrations faced by every writer worth their salt: the slipperiness of language and the inadequacy of words, especially when writing about oneself. It is this tension between her subject and her voice—both irrevocably and forcibly herself—that defines MacLane’s literary legacy.

Ad for Mary MacLane's film. Source: The Mary MacLane Project