Remembering the Swan Valley Massacre, October 18, 1908

Sign on Highway 83 - Photo by Doug Stevens

October 18 marks a great tragedy in Montana history.

In the years following the beginning of the 20th Century, Native rights in Montana came under increasing attacks. Despite rights guaranteed under the 1855 Treaty of Hellgate, Flathead Reservation lands had been opened up to non-Indian homesteading through various allotment acts, and rights to hunt, fish and gather on aboriginal territory outside of the Flathead Reservation boundaries were being ignored and even challenged. At that time, Native hunting parties encountered off reservation were regularly harassed by white settlers.

This was the backdrop when, in September 1908, a Pend d'Orielle hunting party of 8 crossed over the Mission Mountains into the Swan Valley to gather meat for the coming winter, as their ancestors had from time immemorial. The party consisted of Antoine S-tseh-wee, his wife, Mary Tah-pahl, their son, Pelassoweh and young daughter, Little Mary. Accompanying them were elders, Yellow Mountain, his wife, Sahp-shin-mah, as well as Camille Paul and his wife, Clarice, who was six months pregnant at the time.

They made their camp about a mile west of Holland Lake, on the Holland Prairie, north of present day Seeley Lake.

Knowing of the increased antagonism Indians were experiencing at the time, Yellow Mountain even purchased valid state hunting licenses. Yellow Mountain also had written permission from the Agency Superintendent to hunt off reservation. Every "i" was dotted, every "t" crossed, or so they thought.

Area of massacre - photo by Doug Stevens

On October 16th and 17th, a local game warden by the name of Charles Peyton encountered the party in the Swan and set about harassing them. Not satisfied with either the rights guaranteed them under the treaty, and not swayed by the official hunting licenses and note from the Agency Superintendent, he wanted them gone. He informed them on the 17th that he would return again the next day and they better be gone, "or else!"

The hunting party did not want any trouble and decided to acquiesce and leave. By the morning of October 18th, they were all packed up and ready to leave when Peyton rode in with a civilian, Herman Rudolf, whom he had just deputized. After a brief exchange of words, Peyton started shooting. Peyton killed Antoine, Camille and Yellow Mountain. Pelassoweh returned fire, wounding Peyton and knocking him off his horse. Rudolf then shot and killed the 13-year old boy in the back. In self-defense, grabbing her husband's rifle from underneath his fallen body, Clarice shot and killed Peyton as he was reloading to kill her, and the remaining women, too. Rudolf fled into the woods and left Montana.

Clarice Paul then mounted her horse and rode in search of another Salish hunting party. They came back with her to their camp and helped bring the bodies back over the mountains to the Mission Valley. They were eventually buried in the Catholic cemetery in St. Ignatius.

Three months later, Clarice gave birth to her son that January, naming him John Peter Paul.

John grew up hearing the story of the massacre from her mother, but Clarice did not want the story told outside of her family circle, so she swore John to secrecy until after she passed away in 1971 at the age of 96. It was nearly a century later that John came to the Salish-Pend d'Oreille Culture Committee to share the story. He felt it was important for the younger generations to know about what really happened at Holland Prairie. John Peter Paul served as the Pend d'Orielle War Dance Chief for many years before his passing in 2001 (age 92).

Marissa Grant recounting stories of massacre - photo by Doug Stevens

In 2008, Salish and Pend d'Orielle people gathered at Holland lake to commemorate the hundredth anniversary of the massacre. Observances included prayers, a retelling of the events and the unveiling of a historical marker on Hwy 83, north of Seeley Lake, just south of the turn off for Holland Lake, that recounts the events of that October day.

The actual spot is on private land now, about a mile east, behind the sign.

I was very fortunate to visit the area recently with Marissa Grant, a great-granddaughter of Clarice Paul. With the landowner's gracious permission, we were able to walk these hallowed grounds while she recounted the stories she had heard growing up. It is clear that memories of the killings still run deep within surviving family members. One vignette, in particular, stuck with me. Marissa told me that after the shoot-out, her great-grandmother always carried a loaded gun under her dress. She was not going to be caught unprepared ever again. Marissa painted an image of a short, but very strong and brave woman – a woman who still serves as a role model and a source of strength for her, and other young women on the Reservation, when facing tough times of their own.

In the 100+ years since this, and other equally unfortunate incidents of our past, we have hopefully moved forward with a better mutual understanding and respect of culture and preservation of important traditional ways of life.

However, it is never a bad thing to give pause and reflect. I have learned that the story of Clarice Paul is much larger than just this one event and is one from which we can all draw strength and courage.

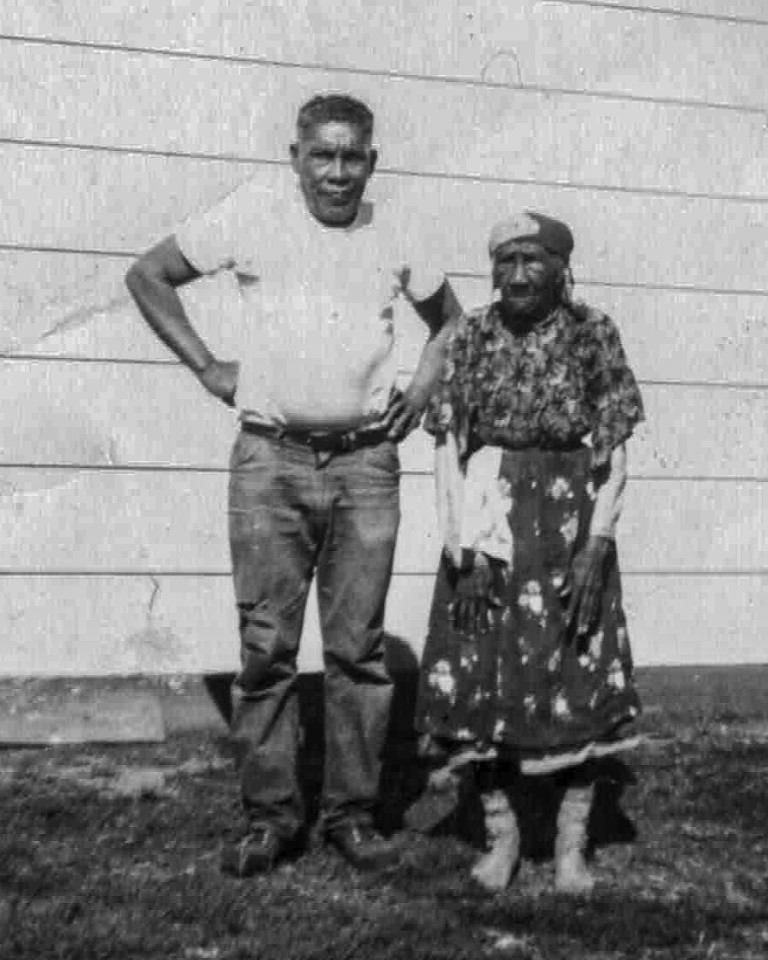

Clarice Paul. Photo courtesy of Marissa Grant