The Day Jack Dempsey Cheated Shelby

To really understand what happened one hundred years ago in Shelby, Montana, you have to first understand that, back then, boxing was big. And we mean big. Because the fights weren't just matches, they were social milieus. People went to the fight to talk, to drink, to pitch woo, to see and be seen. Deals were struck and lovers embraced at the fights. Children might attend, and if they didn't, they were huddled around the radio at home, listening.

So: boxing wasn't just boxing, it was very nearly the national pastime and Jack Dempsey was the undisputed king. In 1923, the very same year he would almost ruin the little Montana town of Shelby, he graced the cover of Time magazine. His fighting style was bob-and-weave mixed with constant, unrelenting attack. It's because of Dempsey's doggedness in the ring that we have a rule that a fighter has to go to the corner and give a downed fighter a chance to get up.

If Dempsey had it made, then Shelby, Montana was on the make. The little Hi-Line railroad town had been on the map since the late 19th century, but had fallen on hard times when homesteading in the region went bust. But in 1921, oil was discovered north of Shelby. Within months, the town filled with oil field workers, geologists, and drillers. Buoyed by the oil boom, Shelby decided to try and become "the Tulsa of the Northwest." Various slick investors and boosters conceived of get-rich-quick schemes involving the sale of whole subdivisions of potential residential areas in Shelby to speculating newcomers.

By 1923, the real estate boom had cooled, but the oil money still flowed. James Johnson, who by many accounts owned most of Shelby, had a son named "Body" Johnson. Body happened to host a boxing event and was surprised by the turnout. Then he happened to see a headline one day - a boxing promoter in Montreal was willing to put up $100,000 (about $1.75 million in today's dollars) if Jack Dempsey, heavyweight champion of the world, were willing to defend his title there. Dempsey declined, but what if the money were better?

In truth, all Johnson and his cohorts were expecting from the offer that they made to Dempsey's manager, Doc Kearns, was another headline, and to see Shelby's name in newspaper print across the country. They certainly didn't think that they would get an answer from Dempsey's people when they sent him a telegram offering him an astonishing $200,000 to fight in their town. This was, as historian Jason Kelly writes, "a sort of practical joke for civic enrichment." But when Kearns wrote back, they found themselves in a tricky position - if Dempsey accepted, they were on the hook for a lot of money.

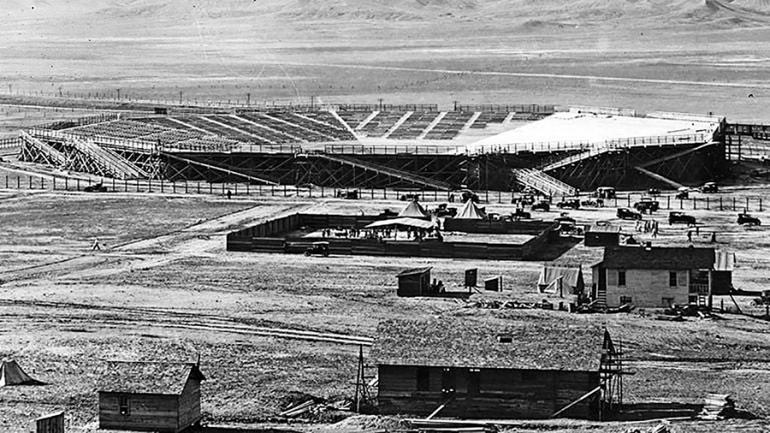

Because, of course, it wasn't just about the money in the boxer's purse. The sheer infrastructure needed to pull off the scheme would dwarf the amount offered to Dempsey. Shelby at its most affluent was still a town of only 500 residents. Some estimates suggested as many as 40,000 could descend on the town to watch the match. There was the expense of a massive stadium, Dempsey's housing, even 35 miles of extra siding to accommodate parked trains.

In a flurry of tricky moves, Dempsey's manager agreed to the match, provided someone from the Shelby camp would travel to New York City and pay Kearns $100,000 upfront. The remaining $100,000 was to be put in Dempsey's purse, payable later. If Shelby were unable to host the match for any reason, the initial $100,000 would be paid to Kearns. Then Kearns sent the telegrams asking Dempsey to fight in Shelby to the Associated Press. Soon newspapers all over the country were writing about the event.

A Great Falls American Legion representative named Loy Molumby was dispatched to New York, where he found himself in way over his head. Somehow, he returned to Montana having promised Kearns and Dempsey another $100,000.

And until he got this third $100,000, Kearns wouldn't announce publicly that Dempsey had committed to fighting, even as hundreds of carpenters were working on building a 40,000-seat stadium made entire out of wood in relatively treeless Shelby. The stadium would end up costing another $82,000.

If Kearns wouldn't publicly speak about the fight, then the trains were reluctant to sell tickets to Shelby. Yet if thousands and thousands of people actually did attend the match, much more rail passage would be needed. Body Johnson concocted a plan to sell help pay for the second $100,000. He would sell that amount in tickets at American Legions throughout the state, so he chartered a plane to take him to every post. After his third stop, his plane flew into a power line and crashed. Johnson was injured, but not mortally. In the end, they were able to make the second payment only after James Johnson agreed to put up half.

On July 1st, three days before the fight, Kearns still hadn't gotten his money yet. So he canceled the fight. Shelby panicked. By then, they had already offered Kearns almost everything they had. They had even asked him to take 50,000 sheep instead of the money. Kearns declined with savor. "What the hell am I going to do with 50,000 sheep in New York?" he asked at a Great Falls press event.

James Johnson resorted to desperate measures, leasing his properties and businesses, and borrowing what he could. He came up with the third $100,000, but if the scheme failed he'd be more or less ruined. Kearns was satisfied. The fight would go on after all.

Of course, lots of folks had just canceled their tickets when they heard that the fight was off.

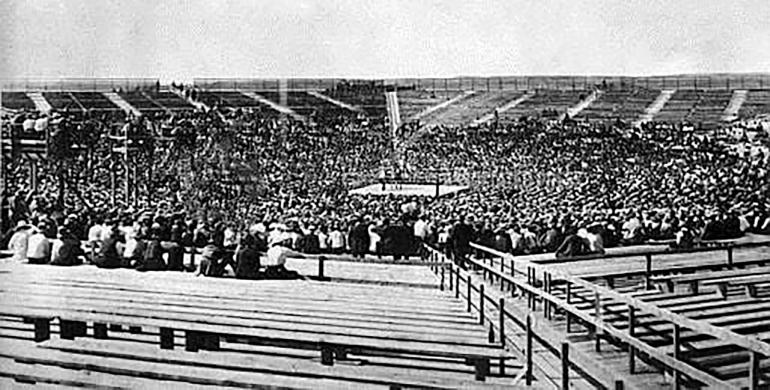

On the day of the fight, the projected 40,000 people swarming the town was more like 12,000.

There was at least one small bit of hope - the Shelby camp had negotiated the rights to the film made of Dempsey's match against Gibbons. They hoped to recoup some of their losses by distributing the film across the nation.

July 4th was a hot day. One sports writer said that his typewriter was too hot to touch. Even though only a fraction of the projected audience showed up, the town was busy and full. Lines for lunch counters led out into the street, while makeshift box offices lined the streets like lemonade stands. Many who showed up didn't have tickets, and many who did have tickets had bought them as an investment, sweeping up whole blocks of tickets for thousands of dollars. Some without tickets chose petty theft, like "One-Eyed Connelly,*" who donned the attire of an ice salesman and, carrying a big block of the stuff on his shoulder, simply snuck in. Those with extra tickets were desperate to make some of their money back. One man, blessed or cursed with five tickets, sold them all for $50, less than a fifth of their set price.

Crowds assembled to harangue the poor SOBs still trying to sell tickets, shouting to be let in at a discount. They might have had a point; would they rather make some money, or no money? One security guard accidentally advocated for gate-crashing when he shouted, probably intending to be tough, "If you don't have the guts to break in, then stay out." It seemed to have the opposite effect.

The point was rendered moot when the match began, since the people manning the concessions and the box offices ran inside to watch, followed shortly thereafter by the mass of people still trying to buy tickets, waltzing in more or less without resistance.

Dempsey's biographer Randy Roberts wrote that the eclectic crowd was "a mix of oil millionaires, Blackfoot Indians, cowboys, shepherds, hookers and sportswriters," all bunched at the front of the stadium, leaving the rest of the massive, rustic structure eerily vacant. The Great Falls Tribune described it as "pathetic in emptiness," while the New York Times quipped that the presence of Charlie Russell in the audience was because he was a "painter of great open spaces" he now enjoyed "the chance of his life" to see "distance from the vacant benches."

The fight was preceded by a preliminary fight and performances by a band from the Canadian Highlands (bagpipes and all), and the local Elks band. Polite applause fluttered around the largely empty stadium. Finally, as the day wore on and the heat beat down on the modest crowd, the fight began. The movie cameras which were crucial to their plan to make at least a little money back started to roll.

The fight was largely unremarkable, except that Tommy Gibbons proved himself to be a better-than-expected opponent. Dempsey won, as almost everyone thought he would, but Gibbons would go into the record books as the only of Dempsey's opponents to last all fifteen rounds with him. The crowd, such as it was, was cheering just as much for Gibbons as it was for Dempsey, and Chief Curly Bear of the Blackfeet, who had been in attendance, declared Gibbons "Thunder Chief," took his headdress off and placed it on Gibbons's battered brow. As for his opponent, author Jason Kelly writes, "[h]ailed as a hero when he arrived more than six weeks earlier, Dempsey rode out of Great Falls more or less on a rail." But, unlike Gibbons, who settled for $7,500 of the purse, Dempsey was a good deal richer.

In the days and weeks following the match, four of Shelby's banks failed, including James Johnson's. The enormous stadium was disassembled, its boards auctioned off to the townsfolk. Today, there is no sign that the match ever occurred, except that at least some of the extant buildings must have been constructed out of, or patched up with, those boards. Eventually, the town largely forgot the fight that nearly brought it to ruin. Maybe they were all too glad to forget it.

Now that those hurt in the stunt have gone on to their eternal reward, some of the hurt has come out of the memory of the fight. Today, the story is remembered as a real humdinger - one of the great cons in American sports history, and a true Montana tall tale.

But what about the matter of those boxing films that were supposed to save the Shelby investors' collective bacons, the distribution rights to which Kearns gave the promoters in negotiation?

Well, it turns out Kearns knew what the folks in Shelby didn't: federal law made transporting boxing films across state lines illegal. The films were, essentially, worthless.

Perhaps just one more anecdote, then, to sum up.

A day or two before the fight, Butte lawyer Frank Walker had, at the behest of the promoters, tried to get Kearns and Dempsey to see the fight through. He found Kearns to be a difficult man. This was the man, after all, who would later fondly recall having shut down four banks with one fight.

The story goes that the lawyer, driven to his limit, finally told Kearns, "Here in Montana we have trees on which to hang fellows like you."

Kearns looked out of a nearby window at the landscape of Montana's Hi-Line, all sweeping prairies, badlands, and grass.

(*who is worth a Google, but suffice it to say devoted his life to being a professional gate-crasher, sneaking into athletic matches and events without paying, and becoming a celebrity in so doing.)