Building a Miracle: The Construction of the Going-to-the-Sun Road

In early Montana when glaciers formed on both sides of the Continental Divide, one of the glaciers eventually carved, chiseled and sculpted its way eastward down the St. Mary Valley and the other westward down the McDonald Valley. They also tore out the ridge between them and became one giant glacier. When the ice melted, the vast landscape that would become Glacier National Park was created.

Along about 1911, just after the formation of Glacier Park, Superintendent William Logan initiated plans for a road across the park. Prior to then there was just a dirt road traveled by horse or wagon or on foot. The name “Going-to-the-Sun” derives from Native Americans who considered the sun sacred and the path to the closest point also sacred.

When automobiles became the favored mode of transportation, the public clamored to construct a road that automobiles could use. Another pressure came from the surge of settlers brought by the Great Northern Railway to the borders of the Park. Bob Marshall, chief topographer of the U.S. Geographical Survey, recommended a road system to connect all the scenic points in the Park. (We have to acknowledge the loss of much natural beauty and sacredness in the interest of access.).

It took about 20 years and a lot of engineering to build the road connecting the east to the west sides. Some men quit when they saw the icy heights they’d have to climb.

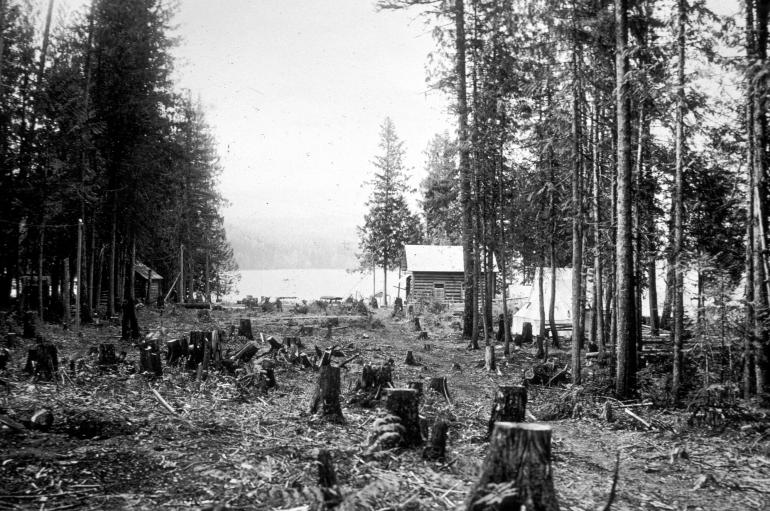

These photos show steps in the arduous process. The Going-to-the-Sun Road was designated as a National Historic Landmark and a National Civil Engineering Landmark

In July, 1933, a big rendezvous was held at Logan Pass to officially open the road to the public. Blackfeet, Kootenai, Flathead, and Salish natives joined the officials in the celebration. Logan Pass on the Continental Divide is 6,646 feet high — and has thrilled (even frightened) many visitors. Anyone in a car or bus could cross the Park in a couple of hours with stops along the way for assorted wonders.

Since then the road has been traveled by millions of visitors. It has endured long cruel winters, heavy snows, and the destructive forces of avalanches, mud and rock slides. It is in constant need of repairs to keep it open and safe. While the road’s original builders have long passed on, now the challenge is to preserve this monumental legacy.

Fast Facts

Road length: 50 miles from West Glacier to St. Mary.

Road width: 22 feet, except for 10 miles along the Garden Wall, which are narrower.

Eight bridges at Belton, Snyder Creek, Avalanche Creek, Logan Creek, Haystack Creek, Baring Creek, St. Mary River, and Siyeh Creek.

30,000 linear feet of pipe and boxed drainage culverts faced with native stone.

Retaining walls of native stone, most notably the Triple Arches and the Golden Stairs.

40,000 feet of historic native stone guard rails.

Road opens 6-21-13. For updates, see FAQ at www.nps.gov/glac/planyourvisit/

Take and Early Tour: http://www.nps.gov/features/glac/eHikes/gttsrhistory/gttsrhistory_final.htm

Sources

Glacier National Park, Legends and Lore,

Along the Going-to-the-Sun Road

by C.W. Guthrie,

Farcountry Press, Helena, 2002.

Going-to-the-Sun Road,

Glacier National Park’s Highway to the Sky

by C.W. Guthrie,

Farcountry Press, Helena, 2006.